Puer, a Post-fermented Tea

- Imperial Golden Tip Pu’er, aka Golden Tip Pu’er, or Gong-ting Pu’er 宮廷普洱 is a tippy fine leaf post-fermented dark tea. This one from 1997.

- Yiwu Daye, Matured Shengcha Pu’er 陳年易武大葉生茶普洱

- Pu’er Grade 1 一級普洱, a moderately matured modern post-fermented tea. Post-fermented teas are traditonally called dark tea. Other names of pu’er include puer, puerh, po-lay, bolay, etc

- Daye Pu’er, baked 焙火大葉普洱

- Xia Guan Xiao Tuo, a single dose version of the compressed dark tea 下關小沱

- Xia Guan Tuo Cha, compressed dark tea 下關沱茶

- Pu’er compressed in small mandarin oranges 普洱小黃桔

- Pu’er shu cha discus, Fuhai 2000

Puer, formally spelled as Pu’er (pǔ-ěr) 普洱, aka Po Lei, Bolay, Pu-erh, Pu Er, Chinese restaurant tea etc, is by far the most known dark tea that is a large subcategory in itself. This article serves as a general introduction to the varieties that are most seen and consumed: the modern loose leaf tea that is post-fermented using a wu-dui process. Some people call this group of teas “shu cha” 熟茶.

a really dark tea

Less than two decades ago, few cared about puer except the people in Hong Kong and nearby Guangdong areas, and emigrants from these places. Puer, initially a low-cost tea variety for the working class in early days Hong Kong, was naturally a staple tea in the dim-sum restaurant, a fundamental Hong Kong institution. It had also been used by ethnic minorities in the southwestern Chinese borders for centuries and used to be despised by others as an unsophisticated tea only for the barbaric south.

This dark colour infusion began to slowly infiltrate the beverage habit in the Chinese mainland in the 1980’s when all things Hong Kong were a hit. By the 90’s, when tea gradually re-gained its appeal in the West, puer was taken notice. Later as the slimming craze picked up momentum, and some show biz celebrities endorsed its effect, the name started to appear in more teashop menus and product lists.

Well, while it is arguable whether the weight-control effects of puer is the best in teas, its more neutral TCM properties and sweeter liquor make it a lot friendlier to more people and thus can be drunk regularly and frequently. Its exotic history and unconventional taste may also contribute to its hype. A speculation trend that has gone ridiculously and catastrophically out of hand also fueled the awareness of this tea in recent years.

For Puer, I mean the real post-fermented tea that the name refers to, not the “Shengcha Puer” that in recent years surfaced. The latter will be discussed in a separate article.

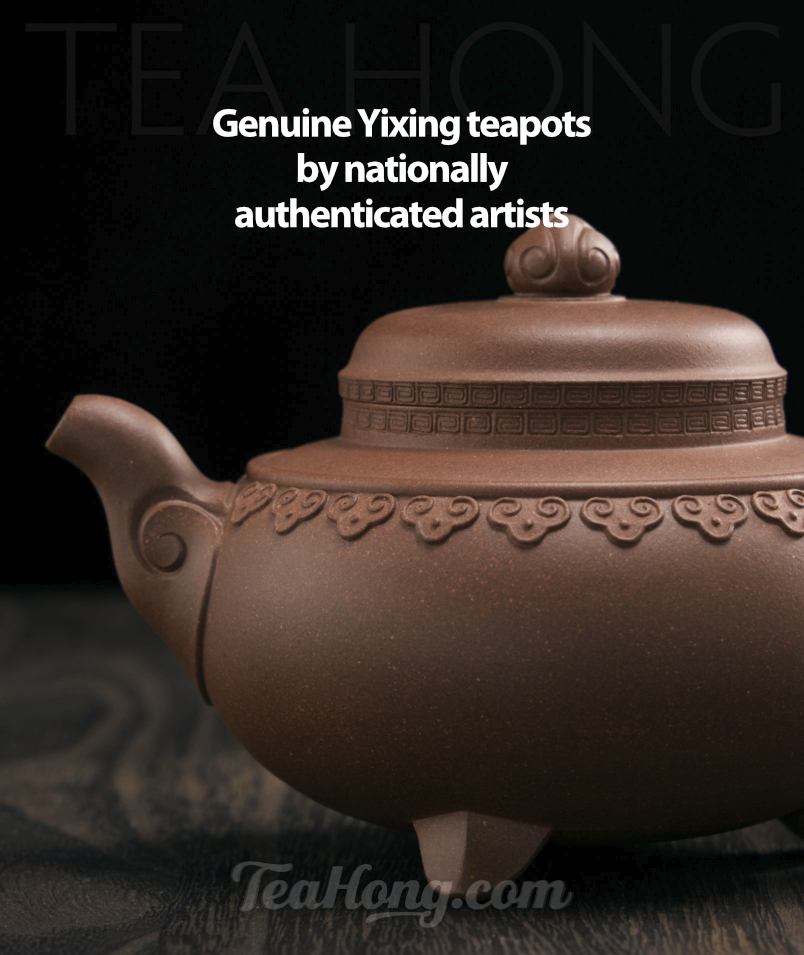

To me, puer is what it has always been. It is a tea that I have grown up with and one that is a household basic. It is one that I can rely on when served in a big pot for continual supply to guests in a party. It is also one that I would take time to prepare well and strong after dinner, in a tiny Yixing pot for a small cup or two with a friend or the family, over a nice dessert (so much for weight-control). It is a most versatile tea.

The demand for the majority of the population who were labourers was simple food. Tea was indispensable for washing down whatever was available to stuff up. Puer was served in all those dark tea cups on the tables. Photographer unknown.

origin

Pu’er is the name of a small town in Yunnan that was once a trading post between the imperial government and various ethnic groups within and beyond the Chinese border in the southwest. Teas were produced for this trading purpose in the neighbouring vast extent of mountains and adjacent provinces; they were referred to by the name of the town.

Through the centuries, the name has become a tea variety that is darkened for less astringency and bitterness. In southeast Asia, it is the tea for degreasing oily dimsums and also a staple drink for pork-eating coolies.

Between the 7th and 9th century, it was unprocessed leaves that the “barbarians” (as the border ethnic groups were referred to) would have to boil in water and seasoned with ginger, pepper or cinnamon (1). By the 16th century, it was documented that although the imperial government’s directives were to use medium grade quality or above for trading, mainly for horses, merchants gathered only extremely low grade tealeaves from various origins that they had darkened for the barters. (2) The package form for this export trading was chiefly compressed tea, and the discus form was a popular one. To appeal to the emperor, however, the finest quality possible from Yunnan was tribute to the royal court each year. Green tea was used for this purpose. Although tea from this province never had the kind of high esteem in the imperial household as those from some of the other key tea provinces had, this sycophantic scheme somehow had maintained the happy profiteering of the traders while holding at bay practical intervention from the central government for centuries. By the early 18th century, government agencies were set up in the major tea production regions around and to the south of Pu’er to protect government interests.

Blackening of the tealeaves happen when these compressed tea “cakes”, packaged in porous materials, got transported on foot through rough and long journey in the vast mountainous areas of Yunnan

In recent years, better quality is more common place and yet profiteering schemes have gotten worse, with similar pampering technique used on the government. In 2009, the authority issued a labeling law restricting that only tea originated in the vicinity of the city of Puer can be labelled Puer. This excluded many products that have been marketed under that label.

It was common sense in older traders that the name Puer was given to teas of various origins that had undergone the post-fermentation process. <Read more about the origin of post-fermented teas> While it was true that some teas with that name were from the vicinity of Puer, but more were not. A large percentage were from other regions. Some were very fine. Now all those previously traded as Puer have to find another name.

The complication does not stop here. With aggressive pushing of the price of Yunnan tea, a “new” label of Puer was born: Shengcha Puer, or Sheng Puer, or Raw Puer. This is basically tealeaves without going through the post-fermentation process, i.e. the crude tea is finished to become a tea on its own before darkening. Products as such used to be called “Shai Qing” (sun-withered) or “Qing Bing” (tea discus before darkening); they were intended for blending, or for darkening by the dealers with their own method or by air through lengthy aging. Some consumers did prefer it raw as such and there are in actuality taste differences in the crude tea. However, with the marketing push, the price point for this new label is now always above the classic post-fermented version, giving the curtails a margin previously unthinkable.

In this site, we refer to Puer only as a post-fermented tea. Shengcha Puer is not Puer. It is discussed in this site as another tea in the label of Shengcha Puer.

@Tames, please read this article:

https://teaguardian.mystagingwebsite.com/what-is-tea/post-fermented-teas-aka-dark-teas/

Another article will be published in a few weeks related to this topic

Hello,

I’m interested in knowing what kind of microorganisms are present in the fermentation of pu-erh. Do you have such information? Many thanks in advance. Best regards. Tames.