Longjing, Tea from the Dragon’s Well

A premium quality Longjing. Notice the yellowish overtone and patches of light grey felt-like materials of the leaves. These are basic signs of a respectable quality. This one from Meijiawu, Hangzhou 杭州梅家塢

lóng•jǐng 龍井, flat style wok-roasted green tea

origin: Hangzhou

Longjing, formally spelled as Long’jing, some spell it as Long Jing, aka Dragon Well, Lung Cheng, Longjin, is the best known green tea from China, and a most imitated one.

gastronomic character

The aroma of the genuine product is warm, fresh, complex and with a note of baked mung beans, or chestnut, and a distinctive accent of bouquet. Properly infused, a fine Longjing has a dense, sharp, savoury full body without being tannic, but an accent of slight astringency. The infusion colour is lime yellow and clear. Sweet at the throat and long, malty aftertaste with a small hint of salt. Since this is a mid-fire roasted tea, let rest for at least two weeks after production before consumption.

orientation

Longjing is a classic representation of wok-roasted green tea. Some say it is the ultimate green tea. Because of its fame and popularity, there is quite a range of fine producers each making what they think is the best Longjing. Since the taste of green tea relies heavily on the quality of the leaves, which is quite strongly related to growing environment, the physical location of these producers become a significant marker of the quality of the raw material.

Better productions from different locations tend to boast how theirs are better in taste and appearance than the others.

Mid-attitude, Meijiawu. This is an important region for the production of a large portion of the accessible finer grades. Notice the taller trees lining sections of the field. This is an important feature that carries a number of functions for the farmers. One being reducing the domination of the tea plant in the micro-ecology. Birds and other preying insects that can find dwelling in the taller trees are vital in maintaining the health of the plants.

However, it is important for the reader to understand that there are huge quality differences amongst various parts of the same farm and also amongst farms within even the same reputable region. There are literally hundreds of Longjing producers just within the Xihu area. Besides the usual consideration of horticultural quality, tea-making mastery, harvesting season, quality management, natural grading etc, there is also the issue of mislabeling. As a result, the claim of any origin has to be verified against the taste.

origin

Although various locations around the Xihu (West Lake) region in Hangzhou has been renowned for tea production since the 8th century, the present way of Longjing making might have come about only after the 15th century, a century prior to the first relevant description of the present kind of Longjing. Its fame escalated when the popular Qing emperor, Qian Long, kept it for his royal use in the 17th century.

Renowned original production locations:

Shi-feng (Lion Peak), Meijiawu, Yangmei Ling, Wengjia Shan, and Jiuxi, all in the Hangzhou area, traditionally referred to as Xihu Longjing (or West Lake Longjing). There is a government assigned labeling system for authentic ones from Xihu, much like an equivalence of the French AOC for wines and cheeses (note). However, judge any buy by the taste, not just the label.

Present day production locations:

Most tea areas in the northern half of Zhejiang province.

tea preparation

Contrary to popular practice, the full profile of Longjing is not obtainable by infusing the tea in a glass.

In Zhejiang, where this tea is produced, people put a pinch of tealeaves into a water-glass and pour hot water in it. The infusion takes place without a cover. People then drink from that glass. This way of making tea came about only about a hundred years ago when having a clear glass was a social status. Coupling that with the look of tender leaf shoots submerged in water, the act was more a show-off rather than about gastronomic pleasures.

The true taste character of Longjing, and for that matter, any fine green tea, is NOT obtainable through this approach. The tealeaves maybe kept greener this way, though, if you prefer the show.

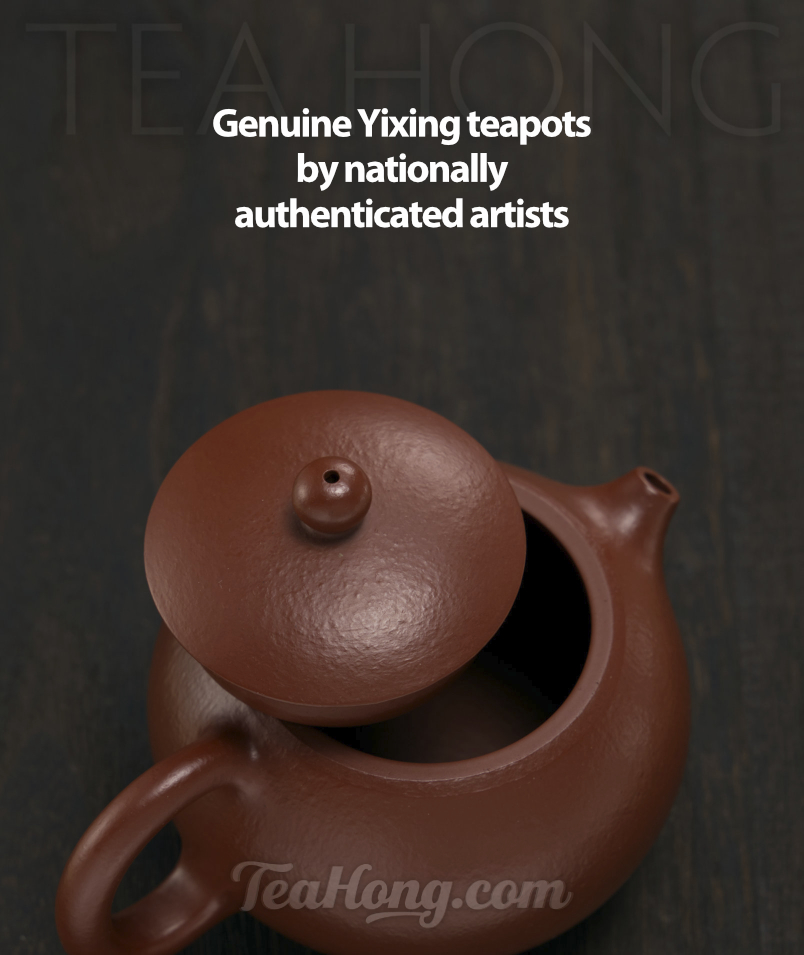

Use a small pot, a taster’s mug, or the traditional gaiwan for better taste. Even a mug with a cover fares better than a glass. A genuine and high density Yixing pot is ideal. Infusion temperature should be kept between 75~80°C. See the Infusion section for more details about maximizing your taste experience.

buying tips

There are both traditional and machine productions popularly available. The former comes in various qualities. The cooking and pressing in the latter are usually relatively over done or not enough. The taste is comparatively less distinctive, coarser and shorter. Over-done ones taste burnt and under-done ones grassy. Different factories, however, would still grade their products with the same grade labels as those by small farm hand-roasted finer productions. A grade 1 from one factory, therefore, would be different from grade 1 from another factory and very different from a good traditional grade 1.

- Long’jing 龍井, a flat-roasted tea, is by far the most famous green tea of China. This one from Meijiawu, Hangzhou 杭州梅家塢 20528 | 8768

- Longjing 龍井 Grade 1 export, of authentic Hangzhou Zhejiang origin 20529 | 8767

- Longjing, Sichuan version 四川龍井. Many places in China produce green teas of various qualities that are labelled as Longjing. This is a very high quality alternative to the original Hangzhou one. 20519 | 8794

- Anji Baicha 安吉白茶, the famous Zhejiang green tea processed to the flat style with a similar appearance as Longjing. 20155 | 8946

In China, where the serving of better tea is a statement of one’s social status, expensive tea is in high demand. Since first flushes are usually finer tastes, there is a belief that the earliest tea is the best tea. Very early tea thus becomes more and more expensive as some people in the society get wealthier and wealthier. However, don’t be mistaken that the earlier and more expensive tea are better.

The flattened leaf of this tea is such a popular visual identifier that a lot of other teas made in this form are quite frequently mis-labeled as “Longjing”. Every year, areas where tea can be harvested earlier than Zhejiang do have their tea made in the Longjing look to be expressed to the province to take advantage of the profitable “early tea” consumer groups. Other productions find their way throughout the harvest seasons all over the country, at the farmers’ market, wholesalers, or exporters, wherever Longjing is wanted. The fact that the name and a similar look guarantee a better price for those involved will be a constant motivation for continual mis-labeling.

Green tea production processing by way of wok roasting using the hand is still a major practice in fine green tea production in China. This picture taken in Hangzhou, home to the finest Longjing green tea

To me, as long as the taste justifies the price, it is fair. There actually are productions outside of the Chinese government defined “authentic Longjing origins” that produce good value and fine quality ones. If you are only beginning to understand the tea, aim for productions that are slightly AFTER the rush for so-called “pre-Qingming” picks, i.e. after late March. The price can be much, much lower, unless you need it to show off to your friends. If you are good in quality-searching, and if you are not so discriminatory of the slightly not so perfect shape Longjings, such timing is a lot more open for good value finds.

On the other hand, I have seen very poor leaves that are labeled as Longjing in retail stores and web-shops outside of China and tasted some of them. I do not know what they are and where they are from, but it seems to me there are cheaters around.

Such similar experiences are one of the reasons why I should spend so much of my time creating this site: the market, whether people of the trade or consumers, need education so the real taste of the genuine products can be experienced and understood.

1 Response

[…] Tea Sommelier, Manuale del sommelier del tè, Tea Guardian, Travel China Guide, Go […]