Understanding Blends, Single Origins, Single Harvests, etc

It’s understood but a taboo in the trade to talk about. When concepts are muddled, it is easier for merchants to push higher perceived values of products that are otherwise stuck with lower margins. People do it in all kinds of trades anyways. Most notably in garment, cosmetic, soft drinks, alcohol etc etc. Tea is only kindergarten in comparison.

But who wants to be conned? Knowledge is the basis to consumer intelligence. Nowadays we see usage of terms in tea that seem to make the product a bit more lofty, more value. Let’s look at some basic concepts here so you can decipher which is the real thing.

Blends

Most mass market tea selections are blended, i.e. various batches of tea mixed together in a certain proportion to give a particular taste effect. This proportion is generally adjusted every year according to the resultant quality of the different batches. The ingredients, however, usually stay the same.

For example, an X brand “English Breakfast” is blended with 1 portion of spring harvest from Kericho Kenya, 1 portion of summer harvest from Nilgiri India, 1 portion of autumn harvest from Anhui China and 1 portion of winter harvest from Kandy Sri Lanka. That is the basic formula. In a year when the tea from Kandy is a bit more bitter, the blender may reduce its proportion to 0.75 and increase the portion of, say Anhui and Nilgiri to a combined proportion of 2.25. FYI, this is only a very simplified formula to illustrate the idea, abridging elements such as quality grades, subregions, stock age, and the number of ingredients.

Sometimes even different categories of tea are used. A proportion of products are also flavoured. Some are added with plant materials that are not tea.

Single origin teas

A single origin means not much other than where the tea come from as defined by as restrictive as the name of that origin mean. It is most often used as the opposite concept of blend.

For example, when a product is referred to as a green tea from Japan, it can be any green tea from any of the regions in Japan. Or a mixture of any of these elements. A Fukuoka sencha defines better what green tea it is and from the region of that name. However, it can be any harvest, or any combination of harvests, from any subregions and farms in any quality grade. When a tea is further defined, such as a Yame Gyokuro, then you know it is from a farm, or farms in the Yame prefecture in Fukuoka of a grade of green tea good enough to be called gyokuro, although this can still be much further defined in terms of quality and origin.

Origin is an important label in that some specific region is renowned for a special quality and the name of the place becomes the indicator of a certain standard. Yame in the above example is in itself a statement of the best of quality in gyokuro. Much like Bordeaux for wine or Luzon for mangoes. For this same reason, it is also often abused to label products of whatever quality, from whatever real origin, out of deceit or ignorance.

Single harvest teas

Tea plants in various regions, farms or estates grow in various speed. Some can be harvested every several weeks, some only once a year. The number of times a tea tree / bush is harvested is dependent on many factors, such as the intent of the product quality, geographic conditions and horticultural management.

For example, the label of a single harvest summer oolong from Thailand carries much less quality representation than the label of a first flush tieguanyin from Xianghua. Not only that the harvest is more defined, but also the origin and the oolong type.

A single harvest can be all that is yield from a single tea tree for that year, or one of the several from a season of the year from the whole plantation.

Single batch teas

A single batch tea is the product from one batch of green leaves going through the complete cycle in production processing. The batch of green leaves can be from any origin, any harvest, any number of trees. They can be hand-plucked or machine-cut or collected in any means. The processing can range from industrialised mass production or traditional hand processing in any of the tea categories.

Single batches are also the most traded products between industrial type black tea factories and tea brokers. A batch of, say ‘orange pekoe’ is 3 cartons, each 30 kilos from a so and so factory in Assam would be sold to an importer in Germany who further sells it to an auction house or a tea brand for whatever they want to do with the raw material.

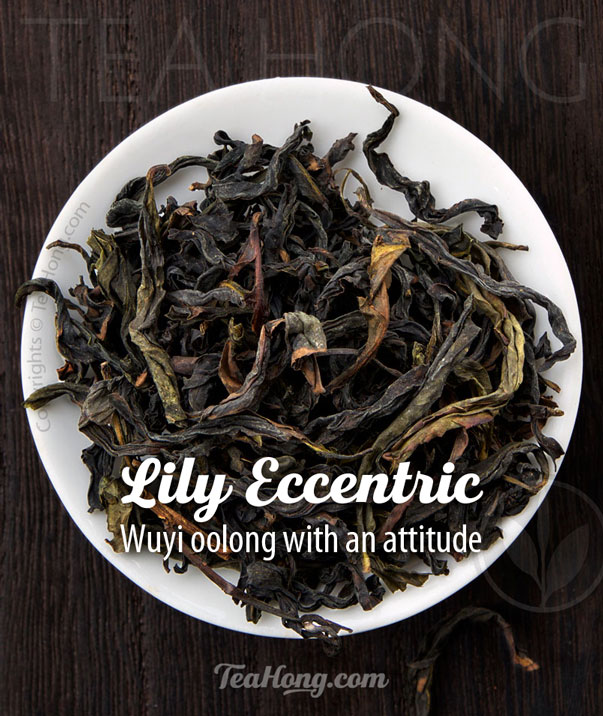

On the other end of the scale, a single batch of spring harvest oolong from a dancong tea tree from Wudong in Fenghuang ( Phoenix ) can be a real rarity because you know that it is the only harvest in the year and even the green leaves from that tree are isolated for traditional style hand processing.

Before I began using definitive labelling in my own tea products in 1999, hardly any other tea traders did more than whatever local law requires, i.e. a best before or consumed by date on a tiny label on the back of the tin. In this past 15 years or so, the trade has come a long way but there is still much room for improvement. We know for sure that for a long time, many products will still lack proper transparency and some traders will insist on purposeful mislabeling or mystification. Many others will still be too under-informed to do better. However, change can also happen from the consumer side.

I hope these few items of definition will help you to define at least the taxonomy in the label, and from there be able to demand better.

Leo Kwan © 2015