Lapsang Souchong, The Original Version

The colour of infusion tells a lot of the quality of a tea. These three teas have all appeared in the previous page as tealeaves: the original Lapsang Souchong, the top grade smoked Lapsang Souchong and the Bailin gongfu version. Which is which? Tips: theaflavins, the indicator of higher quality in black tea, is yellowish orange; theabrownins, browner in colour, is more abundant in lower quality black tea. Thearubigins, the red colour in all black tea, is of the highest content in all. Answer at the end of the 3rd page of this article.

what is a souchong?

There has been a Western traditional misinterpretation of the term souchong (ie xiaozhong) as being a coarse or big leaf tea variety. So the West had continued to apply that term as one of the grades basing on leaf size or appearance (5), although it is not as frequently used now. The original term “xiaozhong” refers exactly the opposite: small leaf variety. It refers actually to a family of tea cultivars that had existed in this part of Fujian since 1717 (6), before the first black tea was made. Souchong in traditional gongfu black tea production refers to a set of processing steps employing tealeaves of the xiaozhong cultivars.

what does lapsang mean?

As for the term “Lapsang”, it is a romanization of the expression “Inner Mountain” from a Fujian dialect, referring to the origin of the tea, Xing Cun (translate: Star Village), as being deep inside the mountains of Wuyi. Romanization of Lapsang Souchong would be “Nei-shan Xiao-zhong” in modern Mandarin. The initial intention of this naming was thus to differentiate the authentic productions from those in neighbouring areas, which was referred to as “wai-shan xiao-zhong” (ie that from the “outside” mountains). Later the term evolved from “Inner Mountain” to become “Authentic Mountain” (ie Zheng-shan) in the present Chinese name, Zhengshan Xiaozhong. The area of being the authentic origin now has grown from the tiny deep mountain village to other areas in Wuyi.

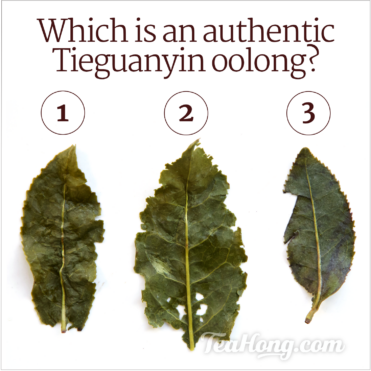

This idea in naming actually had been a Wuyi tradition before black tea. Wuyi oolongs had always been referred to as “zheng-yan”, where “zheng (authentic)” is the same character as that in “zheng-shan”; while “yan” is the character for “big rock”, particularly referring to the heights of the mounts. So teas from the authentic rocks, or authentic mountain, are supposed to be a lot better.

However, Wuyi was only one of the many key production regions with good reputation that the neighbours, whether immediately outside of the small original village or outside of the county, had wanted to imitate. It was only but one amongst all famous black tea regions just within Fujian, ie the famous Minhong areas, all of which also produced their versions of xiaozhongs (7).

smoking with pinewood is only one variety of “lapsang souchong”

Referring back to the tea menus in London in the early days, obviously the tea customers in those days knew only of a kind of black tea called souchong, without any further qualifier as to which region it had come from. And all other souchongs have never had the property of being smoked. It is therefore, reasonably logical to believe, without other solid reliable reference available, that most xiaozhong productions are seen as a generic one, which subtle origin quality difference was understood mostly only by the traders (or just the importers and exporters, and maybe a few tea connoisseurs). Subsequently we can conclude that the distinctive smoked character should be a different thing than the original intent of Zhengshan Xiaozhong (ie Lapsang Souchong). As to whether the strong smoky favour got into the tea by design or by accident as in various fables, it is irrelevant.

This is in agreement with the tradition that is practiced today by the producers: they make mostly clean varieties, especially finer quality ones, with their premium harvests. The large quantity of smoked versions are made with mass market quality chapei ( 茶胚 ie tealeaves for scenting ) from neighbouring areas. Most are not even made remotely close to Wuyi. Of these a huge proportion is scented with additives rather than smoked with pinewood. Almost all are meant for export.