Laos Shengcha

Five years later a few enthusiasts from west of Asia started a business venture to try making shengcha and shu cha pu’er tea in Phongsaly. They see a big business potential in the resource here. I was so happy to such enthusiasm and began communicating with them again. Samples came in. Then a minuscule, sample size order as a test. They have the same problem; in addition to prices a few times higher than what the NGO offered. Shame.

Disappointed, I returned to the small batches from the NGO and was pleasantly surprised.

After the study in 2010, we had put away the small test batches as routinely in storage for other shengcha and white teas, undecided on what to do with the tea. Somehow after 5 years, our storage system has transformed the spoiled maocha into very fine shengcha pu’ers.

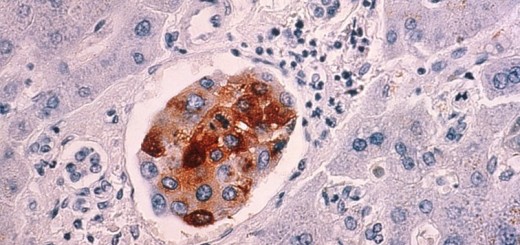

Infused leaves of three Laos shengcha ( left to right ): Phongsaly, Xayaboury, Xieng Khouang

Notice the lighter colour and softer structure of the Phongsaly. By contrast, the Xayaboury which leaf size is similar, has more stiffness and darker colour. Both are spring tea, this suggests that the cultivars may not be the same and the Phongsaly are relatively younger leaves. XiengKhouang has the youngest leaves, because they are basically leaf shoots. Yet they have the most rigid body off the three and a lot more oxidation prior to the heat-involved processes.

the taste

Before I describe the taste of these happy surprises I have to state that I tasted almost 30 of the NGO’s “best” quality samples and found only 3 that could pass my requirements. The sensory quality of the infusions from the others are either almost okay, doubtful or downright awful. The taste told me that there was much to improve on the basic skills. In order to best appreciate what Nature has to give, human efforts is required after all.

Generally all three have clean, fresh earthy aromas that are dominated with a hay overtone. Some are more floral than others. Not unlike those of better white teas, aren’t they? These shengcha selections, however, have a bit more complexity with added accents each of their own.

The one from Phongsaly has a most wonderful floral aroma, with tones of gardena and lily. That goes for the one from Xayaboury too, though not as noticeable. The typical shengcha scent with overtones of prune and jujube is present in both as well. The body of these two are soft and sweet, again with that jujube note in taste. The one from Phongsaly excels with a silky tactility is very round. The aftertaste of both are sweet. A tint of mandarin orange gives the Xayaboury some added dimension.

The sharpness of the Xieng Khouang has subdued little through this five years and remains a nicely strong, sharp tea. I have previously not noted a very powerful pine smoke in this tea. It is here now after maturing to give an overall character for this tea. This is the first time I experience a smoky flavour in tea that gets stronger with time. I still have to learn whether this will grow with time or it will subdue. Then again, its brisk and savouriness have also grown through the years, so has the distinct herbal bitterness.

Like the other two, the Xieng Khouang was produced from wild forest tea trees, with the smallest leaf size of the three. It is the one that has been most oxidised prior to sha-qing. Normally this reduces the sharpness. To have a tea matured for 5 years to taste sharper and more vibrant is a very new experience for me. I guess it has to do with the cultivar and the environment that predestines the taste possibility of a tea.

The biodiversity in this part of the world is yet to be fully appreciate. In tea, this is a new book that we are only turning the cover of.