Renaissance of Dianhong Part 1: the War

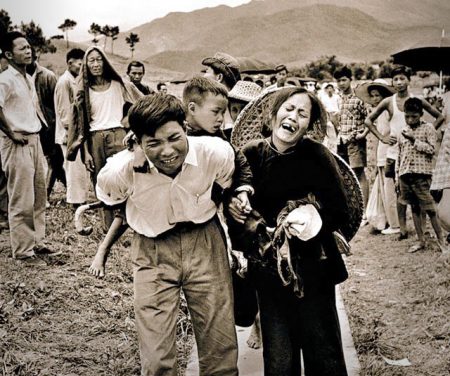

Group Portrait of All Members of the Shun-ning Experimental Tea Factory, November 1940

The county of Feng-qing was called Shun-ning at that time. The man in the middle, with a child standing in front, is Mr Feng Shao Qiu, the director of the factory. People attribute the making of the first Yunnan black tea to him, basing on his own memoir.

In recent years, with the general awareness-building of gongfu black tea in the burgeoning market in China, more producers have entered the game to make different varieties of the subcategory, and that include Yunnan’s very own Dianhong. Competition is keen. Some of the leaves that used to be sold off for producing the pricier pu’er shengcha have now entered the workflow. Much improved domestic transportation has allowed tea masters even in previously more isolated areas to reach out to exchange experience to improve on their products. What was mostly a commodity aiming at the export market in the past 30 years has come to life, perhaps more akin to what it was like when first created in 1939.

Though the original intent was for export revenue, there had been twists and turns in the development of Dianhong.

Japanese Invasion

After the Rape of Nanjing in Winter 1937, Chiang Kai Shek’s government had lost most of the Chinese territories on the east to the Japanese invaders. They established a resistance base further away from the invasion — Sichuan. It was here that many of the “modern” trades and industries established and re-established for the economy and provisions of the resistance government. Tea was one of the export trades that KMT hope to be operable quickly to generate revenue again. The more established tea regions, such as Anhui, Zhejiang, Fujian and Guangdong were all in the East, now under Japanese occupation.

On the other hand, Yunnan, the cradle of the tea plant, was only the next province away, west of Sichuan. Burma Road — which was strategically constructed as a back road for supply when Japan began invading in the East — started in Kunming ( province seat of Yunnan ). The raw material was there, so was the transport. A team had to connect the two dots — turning the greens to product for export sales.

A small task force quickly established the Yunnan Chinese Tea Trade Company in 1938 and experiments of black tea production began in various locations in the vast tea country in the subtropical mountains of the province. History hereon has been obscured and obviously adulterated, as with many other documentation since the Communists took over China. However, it can be verified that one small team was sent to the deep mountains in Shun-ning ( known now as Feng-qing ) in the county of Lincang to experiment with black tea production using local leaves from tree type tea plants. The tea master was Mr Feng Shao-qiu, widely propagated in Mainland China today as the “Father of Dianhong”.

Burma Road: a decisive factor

On closer study of existing texts and data from available sources, Shun-ning could hardly be the production centre during the war. Feng himself wrote that many sections of the “roads” ( footpaths ) were not fit even for donkeys. They had to make “machines” on site using wood, but also mentioned that they had to make do with entirely manual labour. The all members photos we have found simply tells how small the labour force was. The 30 tons of black tea that Feng said they produced and exported through Hong Kong the first year was either pure fiction or from other production centres. One new factory of scale at that time was in Yiliang, 50 km away from the Kunming terminal of Burma Road. Shun-ning was over 500 km away.

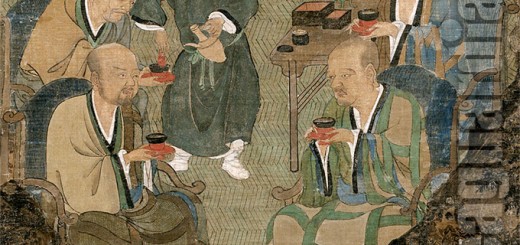

Graduation of Yunnan Technical Training Centre for Tea Production, 1939 at Yiliang Tea Factory

Yiliang Tea Factory was set up properly with tea production facilities, complete with a research tea garden and a training centre. The director was Mr Tong Yi-yun ( probably fourth from left, front row ) who previously managed the Tea Production Research and Development Centre for Keemun. Like many other professionals, entrepreneurs and business owners, Mr Tong’s fate is buried in history since the communist takeover in 1949

Tong or Feng?

It is more likely that the factory director and tea master Mr Tong Yi-yun of the Yiliang Tea Factory played a key role in the major production of Dianhong, if not the real creator of it. Tong had previously worked in a tea production research facility for improving Keemun black tea in Anhui. We have not been able to find other trace about Tong’s subsequent fate or related documents. Many more important people in various other trades and professions had withered in the turmoil years thereafter. Or someone has bent history for a myth to the advantage of their own commerce.

Victory brand Black Tea

The Victory brand was one of the two black tea brands operated by Yunnan Chinese Tea Company Limited during the war years. The other brand was Golden Horse. The funny looking shield shape on the lower tip of the fat V is the registered logo of the tea company.

It seems to me that the experimental factory that Feng ran was either a plan B, a plant resource centre, or a control modal. According to another contradictory account by Feng, his first batch was one jin ( about 600 grams in those days ) but was most beautiful, fat and strong, and laden with gold colour. That has always been the appearance of Dianhong as we know it. Words alone have never been accurate. The small batch was sent to a major tea merchant in Hong Kong for evaluation, and according to the old tea master’s autobiography, judged as the best black tea ever.

The Second World War brought less interruption to tea production than the Communists. Scholars believe that the famine during the so-called Great Leap Forward alone killed 30 million. Fields were left to weeds while people melt all the metal they could find to make “steel” in their backyards. There were countless mass prosecutions of people being labelled as bourgeoise the decade preceding that, and then the subsequent apocalyptic Cultural Revolution where basically thugs took over virtually all aspects of humanly activities and ruined most. Tea was no exception.

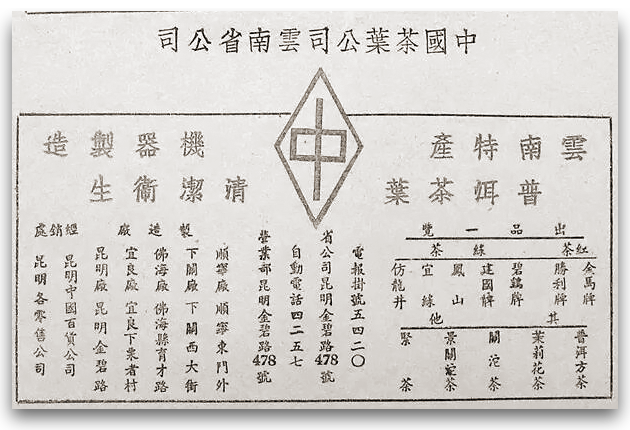

Product list, Yunnan China Tea Company, circa 1942 ~ 45

Of the twelve teas listed, there are 5 green teas, two black teas, 4 pu’ers and one jasmine. The flyer also lists the names and addresses of the tea factories, 5 of them.

One of my tea farmer friends once told me that during Cultural Revolution when she was a child, all the brothers and sisters were trying to grow some veggies and yams on the edges of the tea terraces, on which the tea bushes were left to grow wild. There were hardly enough labour to produce staple food. Indeed, tea were only productions for exports and a few major varieties and grades for domestic consumption for the luckier people.

The entrepreneur spirit of the Chinese people survived. Since the 1980’s when the Communist government loosened the grip on what the farmers should or should not do, tea has come back to where it was left off before the war. It is this condition that has driven the revival of tea production throughout China and let us enjoy the quality as we know it today. « Read Part 2 »