Wuyi Meizhan

Aaron, a proactive young man from U.S. who has been working for some years in China and trying to setup a tea production base in Wuyi, was blank when I told him the name of this tea he was tasting. Never heard of it.

He is not alone, actually. Not many people have heard of a Meizhan from Wuyi.

A Traditional, Lighter Oxidation Oolong

Wuyi Meizhan ( Chinese: 武夷梅占 ) is a lighter oxidation traditional oolong. When properly processed and baked, has a floral character with a unique umami taste and a touch of spiciness. Quite distinct for a Wuyi oolong. However, it was not even a Wuyi local plant until maybe three centuries ago.

Long before Wuyi was known for its “famous” single bush shuixians such as Dahong Pao ( Chinese: 大紅袍 ) or Tie-luo-han ( Iron Buddha 鐵羅漢 ), it had been a production base for commercial grade teas for export. It began with replicating the popular export grade green tea Songluo and later shifted to oolongs. ( Read more about the history of Wuyi oolong )

As to when specific cultivars, including the broadly used shuixian group and the then more exotic ones such as Tieguanyin ( 鐵觀音 ), Qilan ( 奇蘭 ) or Meizhan ( 梅占 ) were first introduced to the Wuyi area has not been indicated in known documentations. We believe it began in the seventeenth century when south Fujianese were forced to an exodus from their homes towards inland. Wuyi was a beneficiary to the Manchu imposed shifted frontier on the south China sea front ( kind of scorch land policy to fight the Chinese resistance ). It received the new tea plants and human resources needed to transformed their tea “industry” just in time for the later bloom in export trade for “black” tea ( i.e. oolongs in those days ). ( Read more about this part of tea history in Minnan oolongs chapter )

A Migrant Cultivar

Exchange of cultivars between regions has been more systematically conducted since after the first republic in China. Between the important oolong regions, i.e. Phoenix ( Fenghuang ), Wuyi and Anxi-Minnan, such activities have become more intense since 1980’s.

Meizhan, said to have originated in Anxi, has been in Wuyi before that time. In Anxi, this cultivar has been under the collective label “Sezhong” ( Chinese: 色種 ). There are other cultivars in this same label: Huangjin Gui ( 黃金桂 ), Foshou ( 佛手 ), Maoxie ( 毛蟹 ) etc. Unlike its counterparts in Minnan, Meizhan in Wuyi has developed a unique favour and a group of connoisseur followers.

In the later two three decades of the twentieth century, when relative honesty was still more commonly practiced in the trade of tea, Wuyi Meizhan was still a unique tea variety, albeit less popular than Shuixian. Somehow, as more people are paying more for tea, and famous names such as Dahong Pao were sought after, the name Meizhan ceased to exist in teashop menus.

Lesser Known, Higher Demand

Production has still been growing though. It is used for blending with other teas to label as the much rarer Dahong Pao or Tieluohan etc. Where else could these tea merchants get the huge amounts of such rare quality to satisfy an insatiable market as huge as China?

The unique taste profile of Meizhan makes the blends more convincing, as long as the originals are not known, there is better chance for the consumer to believe his different tasting purchase, whatever the price, is the genuine stuff. That goes not only for the rare bushes, but for Meizhan as well. The less this Meizhan has been tasted, the easier it would be for the traders to promote their blends as the genuine stuffs.

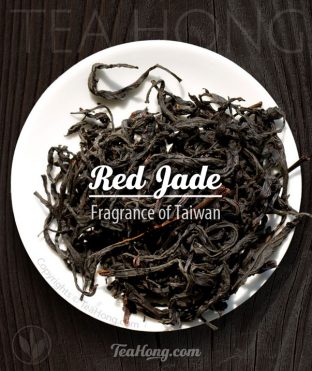

The infused leaves of traditional oolong Wuyi Meizhan reveals the degree and manner of oxidation in the production process

A Unique Taste Profile

A properly processed Meizhan that is freshly harvested would still show a large proportion of yellowish green ( non-bruised leaf structure ) in the infuse leaves. The baking should be deep enough for the tea to mature but not burnt. Its umami taste can be brought out in stronger infusion, usually with more leaves, as most people doing the gongfu style would use. Using the 1 to 100 proportion with 5 to 6 minute infusion time can do the same. However, more leaves and shorter time does reveal better floral character and a cleaner palate.

As with all traditional oolongs, proper heat control throughout the infusion process is critical for the best taste profile, especially with a Wuyi. Unlike any of the shuixians, Meizhan does tolerate fluctuations to yield liquor with lesser bitterness and astringency. This is another reason it is popular amongst blenders.

Because of its lesser fame, even a top quality Meizhan cannot reach anywhere near a medium price Dahong Pao. It is a much more enjoyable tasting experience though. Non-blended teas have always been more distinct, presenting its true self in the liquid that is the fruit of all the hard work and skills between the bush and the cup.