Black Tea: Between Teabag and Hand-rolled Whole-Leaves

Black Tea, aka Hong Cha, i.e. Red Tea (1), is the most consumed tea category in the world and one that is arguably the most versatile in usage.

Most people who drink this tea are used to a “strong brew” prepared usually from broken grades which are inherently more pungent and tannic. And higher in free roaming caffeine ions. The other opposite can be stale or dull tasting tea colour liquid prepared from teabags.

What Black Teas Are Originally

However, this is not what all black teas are like. There are fine quality ones that are pleasant tasting with full body and individual characters, dependent on the make and origin. This used to be what all black tea was about before deterioration of the production process as it was transferred, mechanized, automated, and ‘economized’. This had happened since Europeans taking what used to be an artisan production in China and turning it into mass production in their colonies in the 19th century. The nature of this kind of black tea has since changed dramatically. Most people just adapt their palatial culture to what is easily and cheaply available.

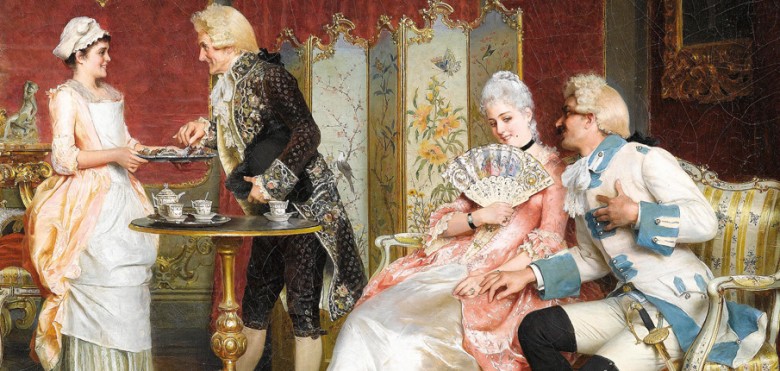

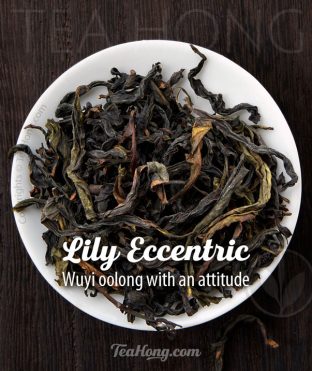

Real tealeaves: the difference is clear, naturally. The salutary substances of tea, as well as those for taste, are much more intact and preserved in a whole leaf than broken ones. Tea: Zhenghe Gongfu, a black tea

In fact, the human taste sensibility can be so forgiving that in the early 18th century when the British government imposed heavy import tax on tea, and when the demand was so high, it was not uncommon for wholesalers and retailers to put all sorts of things into the tealeaves to expand its volume to satisfy the quantity needed by the market. The materials they used included various toxic chemicals, leaves of other plants, re-used tealeaves, and even sheep dung (2). An ex-tea plantation manager Roy Moxham has some explicit accounts about tea commercial crimes of those days in Britain in his book “Tea — Addiction, Exploitation and Empire”. Tea advocate Jane Pettigrew has a lighter writing of it in her book “a Social History of Tea”, if you are not up to the horrid descriptions of the former.

Anyway, let’s refocus our positive energy and look at how black tea has come about and what it really is.

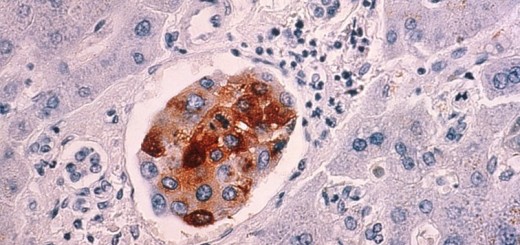

a fully “fermented” tea

By definition, a black tea is one which original tea leaf biochemical contents, such as polyphenols, are oxidized by its own enzymes. Traditionally it is made by withering the leaves so that they become quite soft for curling and twisting. When the leaves are twisted ( or ‘rolled’ as referring to the old way of rolling the leaves into a ball in this step of the process ), the cell structure is broken, allowing leaf enzymes to come into contact with other leaf constituents, triggering a sequence of oxidation. The leaves turn from green to reddish brown. People have misnamed this enzyme-triggered oxidation process “fermentation”, but since the word has been used to describe this tea making process for one and a half century by the West, we shall follow that use here. A black tea is a fully “fermented” tea.

A fine black tea gives a reddish brown infusion with a golden yellow surface perimeter. It should yield a full, malty and vibrant taste with a silky or even velvety texture. However, the character varies from one selection to another depending on the make, origin, cultivar and the season. Click to continue