Oolongs: Minnan (Anxi) Varieties

Infused tieguanyin leaf with flower buds One distinctive visual character of tieguanyin is the beaten edge of the tea leaf. The pluck is almost always two to three leaves, some including the flower bud, as in this case; this is very different from the single leaf in traditional oolongs.

Anxi 安溪 is the name of a small region in the south part of Fujian province (Minnan). Oolongs which leaves that are shaped into loose ball shapes originated from here. Nearby counties are aggressive producers as well. Collectively oolongs from this region is known as Minnan oolongs, or Anxi oolongs.

orientation

Minnan oolongs is dominated by the presence of Tieguanyin ( 鐵觀音 aka Iron Goddess of Mercy, Teguanyin, Tit-koon-yum, etc ), a highly aromatic variety with velvety texture and distinctive flavour. Almost all other varieties from this region of Minnan look somewhat like this tea although they taste a little differently.

A properly baked winter harvest Tie’guanyin, the Minnan oolong from Anxi that is a tea connoisseur’s standard stock.

This is the de facto gran cru tea range for most tea connoisseurs in Southern Fujian, Guangdong, and Southeast Asia. All people who practice gongfu tea infusion would use this tea at one point of time, if not forever. For this reason, it is also the most imitated and adultered tea from Fujian. A fine one is a worthwhile find.

Other popular varieties include Maoxie ( 毛蟹 ) and Huangjing Gui ( 黃金桂 ). These, together with various trade varieties, are grouped as Sezhongs ( 色種 ). Sezhongs are often used to blend in more costly selections to either reduce cost or to add taste complexity. Unlike other oolongs with much longer tradition from older cultivars, fine Minnan oolongs are much easier to prepare with pleasing results.

exodus, economic tides, and the birth of a tea (1)

In 1644, warriors of the nomadic Manchu invaded Beijing to takeover the rule of China from the Ming dynasty. Ming generals and aristocrats in the southern part of China continued the resistance until they were driven to the coast. While the Chinese was experienced in naval warfare, the horseback aggressors hesitated on the pursuit. Rather than upgrading their own navy capability, the new Beijing court came up with a massive plan to rid the resistance: isolation. They forced coastal populations in the south to move inland to isolate the enemy forces. In 1660, survivors of over a decade of wars (2) who lived within 15 miles of the southern coasts undertook a massive exodus to inner counties (3). In Fujian, the people of Anxi, a coastal county immediately neighbouring the closed ports of Quanzhou and Amoy (aka Xiamen), could not be exempted from this exodus.

A Dutch rendition of Konxinga ( aka Zheng Cheng Gong 鄭成功 ), the famous Ming general defying the Manchu rule, capturing Taiwan from the Dutch to turn it into a resistance base.

The monk and tea advocate Zhao Quan (aka Ruen Wen Xi) was 33 at that time (4). He was amongst the Minnan migrants bringing with them oolong production technique to Wuyi, a natural escape. He later wrote a poem about Wuyi tea production, “Recently tea processing has been influenced by that of the bouquet south Fujian (Minnan) style… achieving the fragrance of plum blossoms and orchids, baking to fix that aroma in a basket on a caldron over a red fire…” This maybe one of the first documented mentioning of something similar to the baking step of the oolong production process. No mentioning of tea with similarity of oolong characteristics appeared in any documentations prior to this.

the driving force: export

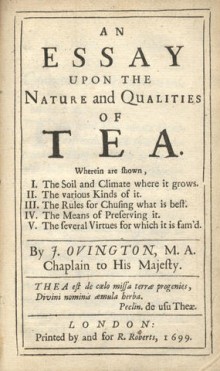

Quite immediately after the West began to import green tea from China, they began to import a black tea by the name of Bohea. That should be before 1699, when John Ovington, Chaplain to King William III, wrote of its medicinal qualities (5). Half of the tea consumed in Britain was this “black tea” as the beverage began to be popularized at a staggering pace. By 1721, before there was mentioning of other “black teas” in English or Chinese documents, legal tea imports to England was 1.2 million pounds, and at least another that same amount was smuggled in. Plus an unknown amount for the Southeast Asian markets, which tea import activities took place even before that of Europe, though unsystematically documented (6). So a conservative estimation of an export need of 2.4 to 3 million pounds should have been the production amount.

Considering the oolong production capacity of Wuyi at 1.2 million pounds a year even in 1990 (7), there was no way that the “black tea” in 1721 was entirely from Wuyi. All other places that could produce oolongs had been recruited to produce to fill this dramatic gap (8).

What place could be better than the home villages of the people who brought oolong production to Wuyi? In 1682, Minnan people were allowed to return home, when Zhao wrote in a Wuyi Tea Song, “Bohea has always been made by south Fujianese… Ships from the West come here (Amoy) every year to buy this tea… so Anxi tea is made to the look of Wuyi tea, roasted before it is baked. The two teas become virtually the same.” (9)

from bloom to recession

Unlike the Wuyi area where oolong cultivars were migrant minorities, a large range of cultivars grew in south Fujian. However, different sayings about local oolongs referred to origins at around the mid 1700’s; that is after the south Fujianese returned home from Wuyi after the exodus. However, at the time of Zhao, local teas did not seem to sell well even at a fraction of the price of Wuyi. The major venue seemed to be export in the name of Wuyi tea.

All the while, it was happy because of ever-increasing demands, despite wars and social unrests. By 1860’s, things had a sharp turn. Not only had red tea taken over oolongs to be the major “black tea”, but the successful production in India and Indonesia began to take over Chinese export dramatically. Tea merchants needed to find business elsewhere to survive — the market at home and that in Southeast Asia.

Productions in and around Anxi were inherently cost saving, compared to Wuyi, because vicinity to the seaports in Fujian, which were closed at that time only to trading with the West, but not to that with Hong Kong or Southeast Asia. The domestic distribution and re-finishing centre in Chaozhou was also only 200 kilometers away. In those days this meant at least two weeks less in labour intensive logistics.

a silver lining

The need to re-focus in other markets might have been a blessing for the long-term development for Minnan oolongs. While before it had been the need to push for quantity, now the focus was the discerning drinkers who had grown up with the gongfu tea preparation style; quality was important to win them. Producers since gave up disguising as Wuyi teas and focused on local uniqueness. Famous names such as Tieguanyin and Huangjing Gui were marketed. Fables were devised to complement the mentality of the times, partly to justify the authenticity of the origin, partly to convince a market impoverished by unstable political and social conditions. Goddess helping a poor farmer with a precious tea tree; a poor woman working her way to prosper her husband’s village with a new cultivar that was her only dowry, etc, etc began to appear. Later, as nouveau riche came about in early 20th century, legends such as monkeys being sent to pick the leaves on rare tea trees growing on cliffs appeared to elevate the status symbol of finer Minnan oolongs.

Nevertheless, somehow the refocus in quality and uniqueness gradually gained momentum and a tradition of Minnan oolong was formed towards the 20th century.